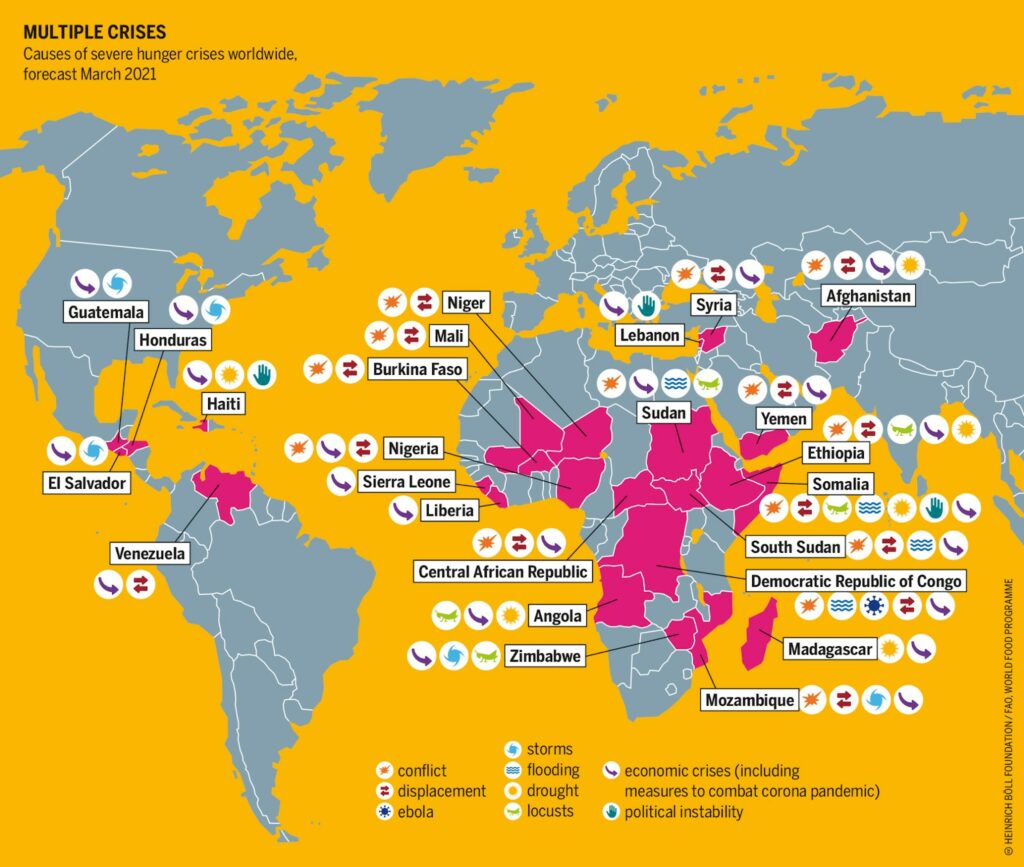

Food insecurity is not a new issue humans are facing. You may have heard the term being thrown around as of late by media outlets due to the ongoing conflict between Ukraine and Russia. Food insecurity is a reality that many living in remote areas and nations under the rule of corrupt government officials have endured for decades.

For those unfamiliar with the term, food insecurity is the consequence of disrupted access to food, which limits the quantity, quality, and cultural appropriateness of the foods available. In 2020, food insecurity affected 155 million people globally at varying degrees of severity with close to 30 million people on the verge of starvation. At the rate we are going at, we will be unable to attain the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal of zero hunger (SDG 2) by 2030 on a global scale.

These numbers give us all the more reason to continue our work at Green Iglu by working towards strengthening current food systems and exploring other avenues of getting food to all humans, since food is a fundamental human right.

Our food systems are already fragile as they are impacted by climate change, energy inflation, economics, labour shortages, among other variables. Increasing wars between and within nations is another significant threat to food systems for it dismantles existing food systems. The effects of war on food production can be direct and significant as seen from the 2013 civil war of the Central African Republic, the cereal production in 2015 was reduced by 70% due to war alone. Additionally, in regions experiencing conflict, infrastructures are decimated to the point where imported and exported goods are reduced or even stopped.

As a consequence of war, the cost of everyday food items skyrocket, crops are destroyed, livestock are removed from their rightful owners, and residents are displaced.

Individuals fleeing from war stricken zones require humanitarian aid, but sometimes the necessary supplies are destroyed or seized by one or both conflicting parties. This prevents them from arriving in refugee camps or affected areas. Despite the United Nations Security Council passing a resolution to denounce the use of war tactics, such as food insecurity and starvation in 2018, wars were still the primary cause of famine in 2020. The resolution encouraged countries currently at war to not target food stocks, farms, markets, and other means of distribution. Those caught ignoring this ruling could be penalised as having committed a war crime. With this in mind, it may take more repercussions to deter the use of unethical war tactics.

We can recall numerous instances throughout history, where targeting the food supply has led to victory, or at the very least a vice gripped reign over a group of people. Perhaps one of the more notable examples is the 1863 Lieber Code during the United States Civil War, in which Union soldiers starved the, “hostile belligerent, armed, or unarmed, so that it lead to the speedier subjection of the enemy”. Another example is the 1975-1979 famine of Cambodia at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. The World Food Programme, UNICEF, and the International Red Cross tried to move emergency food supplies into Cambodia, but could not get anywhere near the daily requirement of 635 tonnes of food, due to blockades inhibiting the delivery of the supplies. The Cambodian genocide saw the loss of 500,000 lives, as a result of the famine alone.

In the present, we are seeing more intra-state conflicts. The rural areas in these war-torn countries are usually at the centre of the devastation, which also happen to be the large food production areas. Common warfare tactics include concealing landmines in arable land, intentionally contaminating or limiting water supplies, demolishing crops, trees, and other physical assets. One of the more recent instances in history is the war in Syria, where more than 6 million people have evacuated their homes to other regions of the country. Those still in Syria face devastating levels of food insecurity. Another 5 million of Syria’s citizens have escaped to different countries. On a global scale, refugees in protracted crises, or situations in which a majority of the population is at an elevated risk of death, disease, and disruption of their livelihoods, increased from 11.6 million in 2016 to 13.4 million in 2017.

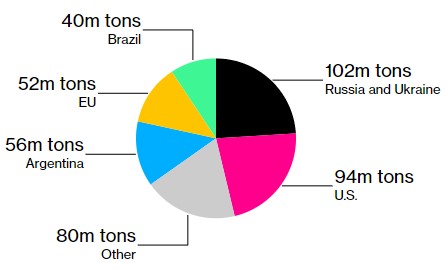

The on-going war between Russia and Ukraine has already turned millions of people into refugees. Russia and Ukraine are significant producers in the world’s agricultural sector, specifically with regards to wheat, corn, and sunflower oil. Russia is a top distributor of fertilisers with inputs of potash and nitrogen, both of which are essential minerals for major crops. Shipments have ceased to occur from both countries, as a consequence of this war. Without these resources, farmers will find it more difficult to grow their crops, ranging from coffee to rice and soybeans. The combined exports of Russia and Ukraine equate to more than a tenth of all calories traded world-wide, which has earned them the title of breadbaskets to the world. Due to the reduced costs that Ukraine and Russia offer their wheat exports for, countries in the Middle East and North Africa, including Egypt, rely on trading with these nations. Other grain-exporting nations may take notice of the situation unfolding in Russia and Ukraine and opt to keep supplies to themselves. Again, this would affect the world’s poorest nations that are highly reliant on these imports.

For every problem, there are bound to be solutions, no matter how insurmountable they appear to be. I read an article written by doctors Caroline Delgado, Vongai Murugani, and Kristina Tschunkert, in which 4 recommendations to address food insecurity in wartime were made. The recommendations are developed to facilitate a joint effort of national and international agencies in providing food aid to the civilians affected. These measures would be significant factors in saving lives and restoring the hope of residents for the future – they will have the opportunity to provide for themselves and lessen the grievances on which non-state armed groups (NSAGs) are thriving. The goal is to reinforce the design of livelihood programmes that cater to different conflict and peacebuilding environments.

Such programmes would be more adaptive to the ever-changing landscape of employment and livelihood opportunities, as a result of faults in the food system connected to agricultural production. By all means, this list is neither extensive nor comprehensive. The idea is to think outside of the box, beyond the more obvious suggestions of increasing food production yields to fight hunger. In cases where food is available or abundant, how do we plan on improving the accessibility of these resources? People need an environment that allows them to produce a sufficient amount of food for themselves, earn the means to purchase it, and have a safety net to keep them afloat amidst crisis.

Wars and violent conflicts break down these pillars that are needed to support a long-term strategy to make food security a reality for all. Food is being used as a weapon during conflicts, when it is a basic human right. When basic human rights are being neglected to a country’s citizens, it is our collective duty to call out countries and advocate for and support the international bodies in getting involved.

Please consider donating to the Ukraine and Syria Emergency funds by the UN Refugee Agency. This article by blogTO also outlines other methods of contributing to the Ukraine crisis.

References:

https://www.boell.de/en/war-conflicts-feed-hunger

https://www.worldvision.ca/stories/disaster-relief/central-african-republic-conflict-fast-facts

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X19300130

https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/2106_food_systems.pdf